New Minister Questions Raisi’s Pledge To Build One Million Housing Units

Iran’s New Urban Development Minister says the government does not have money to build one million housing units per year as promised by President Ebrahim Raisi.

Iran’s New Urban Development Minister says the government does not have money to build one million housing units per year as promised by President Ebrahim Raisi.

Mehrdad Bazrpash, who was approved by the Iranian parliament as Minister of Road and Urban Development on Wednesday, said building four million housing units in four years with cost $80 billion at $20,000 per unit.

Raisi promised to build one million apartments per year during his presidential campaign in 2021, without much consideration to the cost involved.

Asking parliamentarians how this large amount of money can be resourced, he said it is almost twice the amount of the country’s budget this year.

He also mentioned that around 240 thousand previously built government housing units remain unfinished, and the parliament should think of a resource to complete them.

Driven by former President MahmoudAhmadinejad’s populist vision, a project called Mehr was launched more than decade ago seeking to enable homeownership for the economically “oppressed”. The project proved to be a failure do to bad planning and mismanagement.

The scheme caused prices to soar, enabled corruption and profiteering, and made affordable housing out of reach not only for the poor, but also for the relatively well-off.

Reports say the ministry has not built even one housing unit so far, after Raisi and ex-minister Rostam Ghasemi took office.

From the beginning when the proposal was made, many experts did not take it seriously, arguing that Iran would need nearly $15 billion a year to construct one million units, money it simply does not have amid economic crisis and sanctions.

President Ebrahim Raisi Wednesday delivered a traditional Student Day speech at Tehran University to an audience highly vetted to keep protesting students out.

Students have reported on social media that university security and government security forces vigilantly vetted students before allowing them to attend the speech which uncharacteristically was not broadcast live by state media. They claim members of the paramilitary Basij were brought in from other universities and elsewhere to fill the event hall with supporters.

At the same time, students in a dozen universities held protest rallies amid pressures by security forces and Basij vigilantes.

Surrounded by bodyguards and security forces, Raisi also walked through the campus to give a message of “normality” to the event. In his speech and in response to questions from the constantly cheering vetted audience, Raisi praised his own government’s “achievements”, made promises of economic improvement, accused protesters of “enmity with the country”, and claimed the opposition wanted to wage a civil war in Iran, like in Syria.

In the past three months, over 200 Tehran University students were arrested and 20 are still in detention. Some students have been sentenced to prison terms, others have been put on a list of non-grata students or have been banned from attending classes and using dormitories. According to students, the university released a new list of non-grata students ahead of Raisi’s visit.

“One had to sign up and provide a lot of information beforehand [to get the entrance permit], apparently some were denied, for unspecified reasons, even after signing up in advance,” a tweet said.

Another tweet said someone from among the vetted audience had protested to Raisi for not giving a high position to the ultra-hardliner former nuclear negotiator Saeed Jalil. “As if what protesting students want is [a position for another regime loyalist]”, the tweet said.

Raisi’s speech on Wednesday was preceded by a noisy appearance at Tehran’s Sharif University Tuesday where students, including a female student who had defiantly taken her hijab off, grilled the capital’s hardliner mayor Alireza Zakani about corruption, the Islamic Republic’s support for the Taliban, backing the Lebanese Hezbollah and other controversial issues.

Sharif students booed the mayor when he blamed foreign countries for fomenting protests in Iran, staged a protest on the campus, and saw him off with chants of “Death to the Dictator”, “Death to Khamenei”, and “Rascal”.

Raisi said he had been advised not to attend Student Day events at universities, “or at least Tehran University”, presumably due to the current climate in the country, but had nevertheless decided to deliver his speech there. Apparently, he made his decision after vetting those in attendance.

Presidents’ Student Day speeches at Tehran University, the country’s oldest university, and how they are received by students, has considerable significance in Iran's political scene.

On the first anniversary of his election in 1997, reformist President Mohammad Khatami delivered a speech at Tehran University to highly enthusiastic students during which he warned about hardliners’ use of religion to restrict citizens’ freedoms. It is religion that will eventually be crushed if it is pitched against freedom, he said.

In December 1999, however, he had a difficult time with angry students whose campus had been attacked and ransacked by vigilantes and security forces loyal to the Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, who arrested scores and killed several students in July of the same year.

In a Student Day message Monday, Khatami from his retirement praised the “Women, Life, Freedom”, the trademark slogan of the current protests, expressed sorrow for the “shed bloods”, warned that freedom should not be trampled in the name of establishing security, and criticized the arrest of students and pressure on their teachers.

His successor, hardliner Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, never made an appearance at Tehran University for Student Day speeches. Moderate Hassan Rouhani also had a hard time at Tehran University in 2016 when Basij militia students assailed him even told him not to think of a second term of presidency.

A major leak of secret briefing papers related to the IRGC has stirred a big controversy within the Iranian regime, leading to the arrest of a loyal official.

Last week, Black Reward, a hactivist group released tens of files containing IRGC-linked Fars News Agency's exclusive security briefings for the Guard’s Commander Hossein Salami, compromising some closely held secrets.

One immediate victim was Abbas Darvish-Tavangar, a long-time hardliner media man and analysts who was the second in command at Fars.

One of the outlets that published the files for the public, the online Iranian Studies Library, noted that the security briefing bulletins were prepared exclusively for Salami by a team headed by Tavangar. Individual bulletins were prepared in between 120 to 140 pages daily.

As pointed out by an insider commentator Abbas Abdi, the agency came up with conflicting explanations including denying the existence of the bulletins. "They said the briefings as published contained lies, rumors and inaccurate information. Later they said Salami did not need such information and that they have been prepared by a single rogue element. Some others called the bulletins 'dirty political weapons,' and levelled all sorts of accusations against the bulletins' authors. All that made the matter even more complicated."

Abdi asked a series of important questions. If the content of the bulletins were wrong or if Salami did not need them, why their compilation and publication continued. Does this mean that the news dissemination system is faulty even at such a high level? Also, no matter if the content was true or false, was Salami influenced by the information? The intended audience may have been badly misled by this and other similar bulletins. Have they been the basis of decision making by the intended audience?

If the information was false, did someone deliberately misinform the IRGC commander or the producer of the bulletins simply lacked the editorial judgement and skill for collecting the information? In both cases, using such briefings could have been dangerous, Abdi pointed out.

Referring to the "top secret" classification of the bulletins, Abdi noted that they might have included right, wrong, and unverified information. This does not mean that everything in the bulletins were top secret. But the IRGC assigned the classification to prevent others from finding out its sensitivities and priorities.

Meanwhile Abdi added that the hacking prompted the IRGC to deny the bulletins' contents. He concluded that an organization that is surprised by revelations about its behind-the-scenes operations certainly has a problematic structure.

In another development, conservative commentator Mohammad Mohajeri warned that state officials should treat all such briefing bulletins in a way as if their contents are not true unless it is proven otherwise. He pointed out that false information may be deliberately put at officials' disposal to mislead them.

Mohajeri also pointed out that some of the contents of the hacked bulletins are half-truths and half lies, and this is even worse than giving false news to someone. However, considering Mohajeri's background as one of the former editors of the ultraconservative Kayhan newspaper, and his links to the core of the regime, his comments may be an effort at damage control.

On the other hand, Mohajeri called for an end to the publication of similar bulletins, calling them "biased," although he also opined that the briefings could be helpful if they were authored in a professional way. He said bulletins were being prepared and disseminated to officials for at least thirty years now, and some of them are utterly created to channel their audience's behavior and decisions in a certain direction.

Sister of Iran’s ruler Ali Khamenei has condemned the “authoritarian rule” of her brother saying she hopes to see the overthrow of tyranny in Iran soon.

In an open letter published in Farsi and English on her son’s twitter account, Badri Khamenei said the regime of Ruhollah Khomeini, the founder of the Islamic Republic, and Ali Khamenei his successor has brought nothing but “suffering and oppression” to Iranians.

She went on to say that the people of Iran deserve freedom and prosperity, and their uprising is legitimate.

“My brother does not listen to people’s voice and wrongly considers the voice of his mercenaries... He rightly deserves the disrespectful and impudent words he uses to describe the oppressed,” she added.

“As my human duty, many times I brought the voice of the people to the ears of my brother Ali Khamenei…But after I saw that he did not listen…I cut off my relationship with him,” Khamenei’s only sister told the public.

She further sympathized with the people, saying “I oppose my brother’s actions and I express my sympathy with all mothers mourning the crimes of the regime, from the time of Khomeini to the current era of the despotic caliphate of Ali Khamenei.”

She also called on the IRGC and Khamenei’s “mercenaries” to lay down their weapons as soon as possible and join the people before it is too late.

Badri Khamenei’s husband was a fierce critic of the regime, and her daughter was recently arrested for voicing her own criticism.

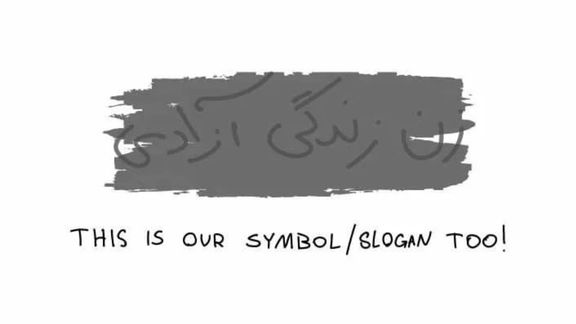

Walls of cities have always been places where people express their opinions; from the ancient city of Pompeii to Zanjan, north-west of Iran’s capital Tehran.

Iranians are well acquainted with the concept of political graffiti and used it extensively during the days that led to the Islamic Revolution in 1979, but these days they are using the medium to overthrow the Islamic regime.

According to documents released by hacktivist group Black Reward last week, the authorities are gravely concerned about the propagation of the phenomenon on the backdrop of nationwide protests and strikes that have rocked the foundations of the clerical regime during the past 80 days.

The confidential briefing papers to the office of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and ranking members of the Revolutionary Guard, acquired by hacking into the database of IRGC-affiliated Fars News Agency, revealed that the authorities seem unable to deal with the enormous number of political slogans on walls and the persistence of protesters to renew them after they are painted over by the cities’ sanitation departments or volunteer members of Basij paramilitary force. In one of the documents, the city of Zanjan was mentioned as an example where almost all its walls are covered with slogans against the regime. Something especially worrying for the regime is the slogans directly targeting Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, referring to him as a “bloodthirsty dictator” or a “despot” whose days are numbered.

Iranians know the significance of slogans against Khamenei, whose zealot supporters are prepared to kill anyone for even criticizing him, let alone wishing death for him. But now, according to the leaked documents, even schoolchildren are using slurs to talk about him. Profanities against the Supreme Leader which were only chanted in the worst protest-riot situations in the past have become mainstream, while protesters are continuously coming up with new and ingeniously rhyming slogans with even stronger profanities. This degree of profanity is unprecedented in Iran where four-letter words are normally avoided in most social and even private contexts, particularly in the presence of women and children.

The regime’s agents are busy everywhere painting over the slogans or doodling over them to conceal the zeitgeist of society, but people are greater in numbers and bolder in action. For every graffiti that is painted over, more or bigger graffiti appear the following day. The most frequently used slogan is the motto of the uprising: Women, life, liberty – words that describe people’s aspiration that no amount of paint can hide them.

Walls have become a new frame for people to make their voices heard. As American linguist George Lakoff explains in his book Don't Think of an Elephant!, that when you frame the debate, you have already won. Its rough translation on street walls of Iran is that however the regime paints over its walls, it cannot change the fact that most Iranians do not want the regime.

According to an article in Etemad newspaper, the calls on Tehran’s municipality's service requesting to remove writings from walls have recently increased 60-fold. The paper cited sociologist Hossein Imani Jajarmi as saying that such an increase “is directly tied to the recent unrest.” Describing political graffiti as a common tool to express economic and political woes as well as racial and gender discrimination, he said the spread of graffiti during the past few months can be a sign of ineffectiveness of the regime’s coercive and military measures.

Over 1,500 instances of political graffiti were found at Pompeii, offering a glimpse into the workings of Roman politics at the local level. Similar to how graffiti shed light on how politics was in the city of Pompeii until it was buried under volcanic ash and pumice in 79 AD, the walls of Iranian cities testify as to how the people fought their way to “Women, life, liberty.”

Conflicting statements abound by Iranian officials about measures to enforce hijab amid ongoing protests ignited by the death of Mahsa Amini by hijab patrols.

Following the recent propaganda stunt by the government that the so-called ‘morality police’ has been disbanded, foreign and Iranian media are full of interpretations of how the regime plans to both enforce the dress code regulations and at the same time appease protesters.

On Tuesday, hardliner lawmaker and member of parliament’s cultural committee Hossein Jalali said that hijab enforcement will never be abolished, ensuring that “veils will be back on women’s heads within two weeks.” His remark shows that a growing number of Iranian women who are appearing in public without hijab since protests began in mid-September.

Confirming that the regime is making some decisions about hijab rules, the lawmaker explained that the methods for enforcing hijab may change, adding that “it is possible that women who do not observe hijab would be informed via SMS, asking them to respect the law. After notifying them, we enter the warning stage... and in the third stage, the bank account of the person who unveiled may be blocked."

Jalali did not elaborate on how the government intends to identify the people who unveil in public to send them text messages. However, there were earlier reports that the Islamic Republic was about to start using cameras in the metro to track and identify women. Such measures had been announced as part of efforts by President Ebrahim Raisi’s hardliner administration to intensify pressures on women in society throughout the year which culminated in the beating to death of Mahsa Amini by hijab enforcers.

On Monday, Ali Khan-Mohammadi, the spokesperson of Iran’s Headquarters For Enjoining Right And Forbidding Evil, tasked with promoting the Islamic Republic’s interpretation of Islamic laws, echoed some reports about the end of the hijab police, saying that "the mission of the morality and social safety patrols (the official name for the hijab police) is over."

He added that new measures will be implemented "in a more modern framework, using the technologies that already exist for this purpose and with an atmosphere that is not one-sided."

Iran's police have so far declined to confirm Prosecutor General Mohammad-Jafar Montazeri’s claim on December 3 that the notorious "morality police" has been disbanded, as international media trumpeted the report. Shargh daily reported Monday that it had contacted the head of public relations of the Greater Tehran Law Enforcement, Colonel Ali Sabahi, to verify the claim but the official refused to make any comments.

The news about disbandment of ‘morality police’ was widely covered by Persian and foreign media as a measure by the Islamic Republic to calm the unrest. However, state-run media immediately cast doubt on any substantial change in hijab enforcement.

Montazeri’s suggestion made headlines in many major international media and even made US Secretary of State Antony Blinken cautiously comment on it in an interview with the CBS.

Many activists, such as US-based Masih Alinejad, have debunked Montazeri’s claim as a sheer publicity stunt or even misinformation spread by a dictatorial regime that is about to fall. However, there are some journalists such as Negar Mortazavi and Farnaz Fassihi of the New York Times who called the measures a victory for Iranians, eliciting condemnations by Iranian activists.

Human rights group Amnesty International has issued a statement regarding the issue, urging the international community not to be “deceived by dubious claims of disbanding morality police.”

“The Prosecutor General’s statement was deliberately vague and failed to mention the legal and policy infrastructure that keeps the practice of compulsory veiling against women and girls firmly in place,” said Heba Morayef, Amnesty International’s Regional Director for the Middle East and North Africa. “The international community and global media must not allow the Iranian authorities to pull the wool over their eyes. Compulsory veiling is entrenched in Iran’s Penal Code and other laws and regulations that enable security and administrative bodies to subject women to arbitrary arrest and detention and deny them access to public institutions including hospitals, schools, government offices and airports if they do not cover their hair.”